THE WORLD OF BASIL TWIST

Text: Matt Mullen | Pix: Jonno Rattman

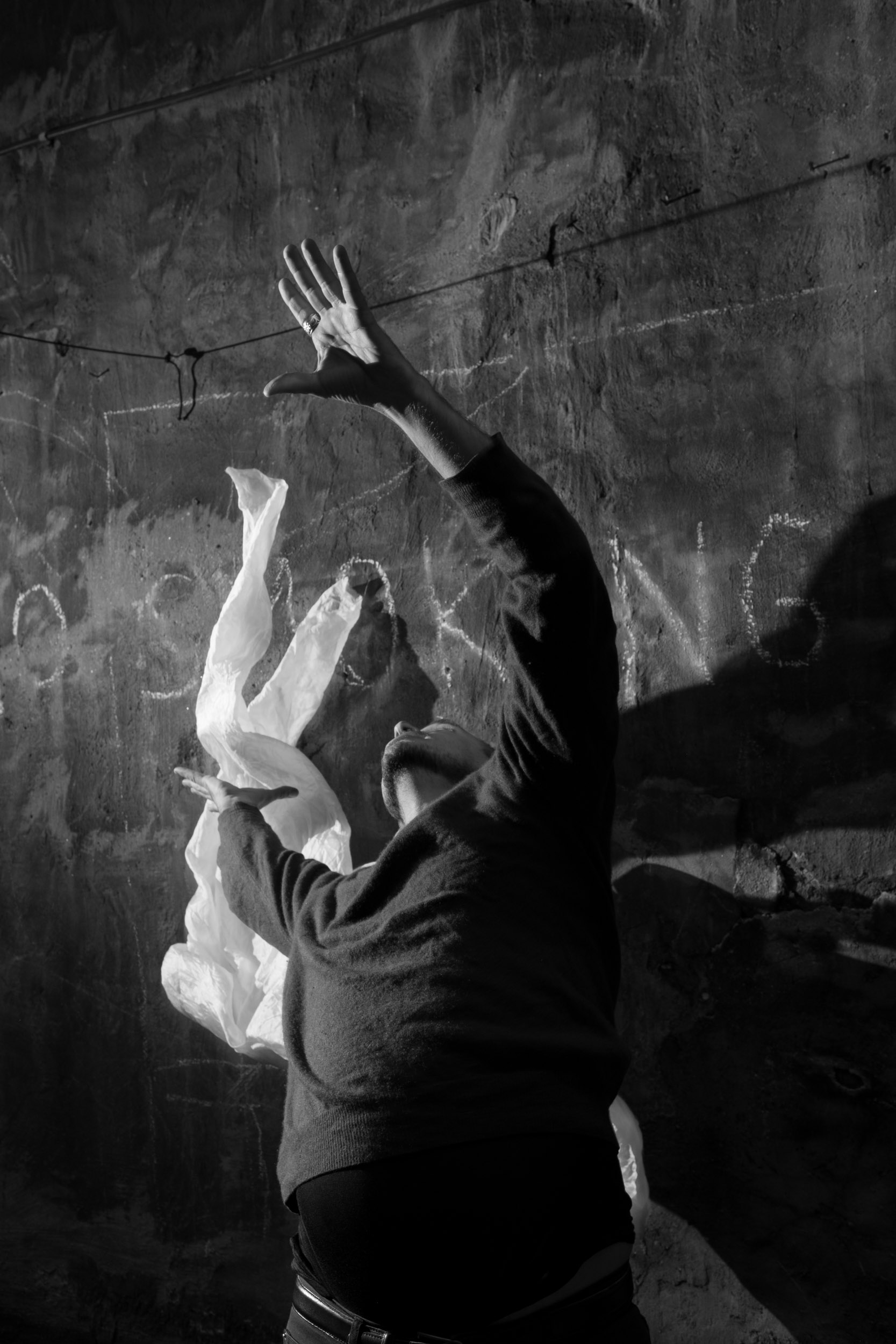

Basil Twist grew up in San Francisco, but for more than 20 years he has lived and worked on Leroy Street in the West Village. Twist is one of the country’s most exciting puppeteers, and easily the most celebrated—with grants, fellowships, awards, and a stream of work that, by and large, has remained steady since 1993, when he graduated from puppetry school in France. And rightfully so: he is singularly gifted, able to literally breathe life into inanimate objects and bring them alive onstage in baroque and fantastical ways. Twist is particularly interested in telling stories through nonrepresentational figures. Instead of using a marionette in the shape of a young woman, he will create a walking and talking character from a lone piece of silk.

After moving to New York, Twist drew inspiration from the downtown queer scene—many of his early shows were performed at gay bars. A mainstream breakthrough came in 1998, with his first big work: Symphonie Fantastique, a carefully orchestrated underwater extravaganza, in which various materials and lights are manipulated through a 1,000 gallon tank. (This coming March, to celebrate its 20th anniversary, the show will be restaged in its original home at the HERE Arts Center in the Village.) Since Symphonie, Twist has produced over a dozen of his own shows and has as collaborated on operas, ballets, plays, and musicals—he is the rare New York artist who can swiftly move between the worlds of blue chip uptown venues (Lincoln Center, Broadway theaters) and groovy downtown ones (La Mama in the East Village, the Abrons Art Center in the Lower East Side).

For all of Twist’s innovative drive and spirit, he remains an analog craftsman at heart. All of his puppets are handmade, and all are operated by hand on or above stage. He is a believer in what he calls the “ancient ritual” of puppetry—the process by which we come together and watch the unreal become real, right before our eyes.

What is your relationship to the city like today? Elements from the world of gay and drag culture inspired your early work. Is that still the case?

Change happens slowly, so you don’t really notice it. I definitely don’t go out as much anymore. But I still feel connected to that group of freaks. I still have friends who regularly perform. The gay nightlife community—that still feels like my family in many ways.

When you do go out, where do you go?

I go to Club Cumming in the East Village and The Monster in the West Village, which is close to where I live.

Your practice has always been very analog. Would you ever consider exploring the digital or technological realm?

Never! I mean, some things about it interest me. I’m curious about virtual reality. I’m curious about different experiences people can have with technology. But I’m just a very tactile person. I like the analog nature of puppetry. I like the ancient ritual of people coming together in a space and lending their presence, the ceremony of that. I guess people can do that with technology—and maybe I even have myself in my work, I’m just not aware of it. But I pride myself on being analog. Even back in ‘98, people would be like, “Wow, this is so analog.” But that concept is obviously way more intense now, as we’re all so stuck in our phones—myself included, all day long. So it’s great to snap out of it.

Symphonie Fantastique turns 20 in March. How has your relationship to the piece changed? Does the piece age or evolve? Has it felt like 20 years?

It doesn’t feel like it’s been 20 years. Like, I have interns who work with me who are 21. I remounted the piece five years ago in Washington D.C., so it hasn’t been totally dormant, and it’s been an essential part of my immediate community—my puppet family. Many, many puppeteers I know and have worked with and are still connected to were part of that show. So it does feel like a person who I’m growing up alongside. I feel all these connections to it, and influences from it. It was such a seminal piece for me, and it’s shown up in lots of other work, too—the sense of abstraction and animation of non-figurative materials. Even though I made an explicit point after Symphonie Fantastique to make something figurative, which was the show Petrushka, I still used a lot of non-figurative stuff in that. And what’s really neat about bringing it back, to HERE, the place it began, is that it puts everything in perspective; like, remember when we used to do it this way? And when the building was different? And when the neighborhood was different? So much time has passed.

Looking at the piece now, are you ever tempted to change things around?

Yes. I will allow myself to change it a little bit. I think it’s more about getting it closer to what I was trying to do in the first place. But the challenge of the show is that it’s very difficult to rehearse, so it’s not like there’s a long process in which I can even change it.

Ideally art is supposed to feel timeless, right? You’re not supposed to look at a piece and think it’s dated. At the same time, good art should be of-the-moment. How do you capture that contradiction?

I don’t know if it’s something I’m consciously thinking about when I make work. I’m not going, “How is this going to look in 20 years?” Looking back at Symphonie Fantastique, which is from ‘98, I can tell we were really close to Y2K and the new millennium—I think that was looming over everything that was happening at the time. But in general I think you just have to do the best you can for the people who are right there when you’re making it. My work is not something you hang on the wall; it’s something where you go in a dark room and sit down and commune with it. You don’t think of the people in that room 20 years from now. 20 years ago I had no idea that we’d all be on Facebook, and that September 11th would have affected things so much, and that our current president would be our president. There’s no way I could imagine any of that.

You've received a lot of institutional support over the years—the MacArthur Grant, for one example. How important has this been to you? How necessary has it been?

I have had a lot of support, but my work—its handmade quality, its labor-intensive quality, the people that it takes, the materials that it takes—it’s consistently costly. People have no idea what it takes. Sometimes they think because it’s puppetry it’s cheap; because it seems like a light word, or diminutive, or it seems somehow second-class. But in Petrushka, for example, each character is operated by three people, so you’re hiring three times as many people—at least. It’s one of the problems of puppetry. Most of the resources that I’ve gotten have gone straight into the work and not out the other side. So yes, I’m super fortunate for institutional support, because I wouldn’t have been able to make the work otherwise.

Is it a restrictive art, then? If it takes so much money and so many resources? What does the future of puppetry look like?

I don’t really know what the solution is—I would just say tenacity and persistence. Puppetry is always going to be a marginalized art. It’s going to have to work in partnership with other forms of art, or on the fringes of things, or as the exception. So it needs to be exceptional—and special. Those things are rare and worthy. That being said, I’d be down with major universities getting behind puppetry, or larger institutions having it be part of their actual structure and commitment of resources. There are, fortunately, for now, some organizations like that: the Jim Henson Foundation, or the HERE Arts Center, or Saint Ann’s Warehouse come to mind. But they do it at great cost and risk. It takes total commitment.

When you studied puppetry in Europe, did it feel more accepted there?

I think this is just generally how it is. Though in Europe—in France in particular—you can make a living as a performing artist. There is a support system for it. The system encourages entrepreneurs who choose to be artists. It’s still hard for them, but there’s definitely way more there.

I’m jealous of people in France.

Oh, me too.

Would you ever leave New York?

Maybe. But I have so much going on here: At the moment I’m working with Mabou Mines on a new show in the old PS 122 space. And I’m working with Julie Atlas Muz and Mat Fraser on a new show of theirs at Abrons Art Center. I’m always helping my friends.