IN CONVERSATION:

JENNY HOLZER + LILI HOLZER-GLIER

Lili Holzer-Glier and Jenny Holzer, who is holding one of her favorite items, a tray gifted to her by school children as a thank you for visiting their class.

When our team sat down to think about text and images, where they intersect and diverge, and the limits and reach of each, we found ourselves at a bottleneck. How could we begin to assess the visual potential of words or the storytelling abilities of images? (We’re still muttering "but what is language" under our breaths.) In short, we had questions. So we reached out to two New Yorkers whose work felt particularly relevant: Jenny Holzer, a visual artist who deftly coaxes words into public installations, and Lili Holzer-Glier, a photojournalist who sensitively evokes her subjects’ stories. The mother and daughter recently got together at Holzer’s apartment in DUMBO to kindly ask each other our questions while posing a few of their own.

You can look forward to a retrospective of Holzer’s work at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao come spring 2019, and Holzer-Glier’s photographs will be on view closer to home in “The Way We Live Now,” a group show at Aperture opening June 27, followed by the release of her photobook, I Refuse for the Devil to Take My Soul (powerHOUSE), this fall.

JENNY HOLZER: Lili, when did you realize I am an artist?

LILI HOLZER-GLIER: I think it's something that I always just knew.

HOLZER: What did you think of my work?

HOLZER-GLIER: As a child I cared about you as my mother, not as an artist. I appreciate your work now that I'm older.

HOLZER: Good answer. Did we talk about art?

HOLZER-GLIER: It depends on what age we're talking about. I think from maybe 14 on we had successful conversations about art. Before that, I'm not sure. Tell me if I'm wrong though.

HOLZER: I can add that you knew about Ad Reinhardt when you were six and you said you "liked him the very best." Lili, did we visit galleries or museums?

HOLZER-GLIER: Yes. My most vivid memory is going with my father to a museum in Berlin, and I threw such a hissy fit about hating museums and art, and asked “why do I always have to go to museums?” that he promised never to take me to one again. [both laugh]

HOLZER: I recall that report vividly. I believe it is absolutely true.

HOLZER-GLIER: Jenny, is there anything you felt you wanted to teach your daughter about art at a young age?

HOLZER: Oh, I have the answer to this. My mother always said with great excitement, "Look! Look!" Usually not about art, but about something marvelous in the world. I wanted to teach you to “Look! Look!” Lili, what is your favorite work of mine and why?

HOLZER-GLIER: I like the LEDs because it's a perfect marriage of language and visual excitement, and it's completely original, no one else's work looks like that.

HOLZER: I especially like Lili's recent photographs of inmates in a jail in Chicago, because seeing those might actually help.

HOLZER-GLIER: How does text play into your practice?

HOLZER: A big question. I like explicit content, and with language you can be quite explicit. Okay, your turn: Do you have any text in your stuff?

Jenny Holzer, New Corner, 2011 (detail). © 2011 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Sang Tae Kim. Courtesy of the artist.

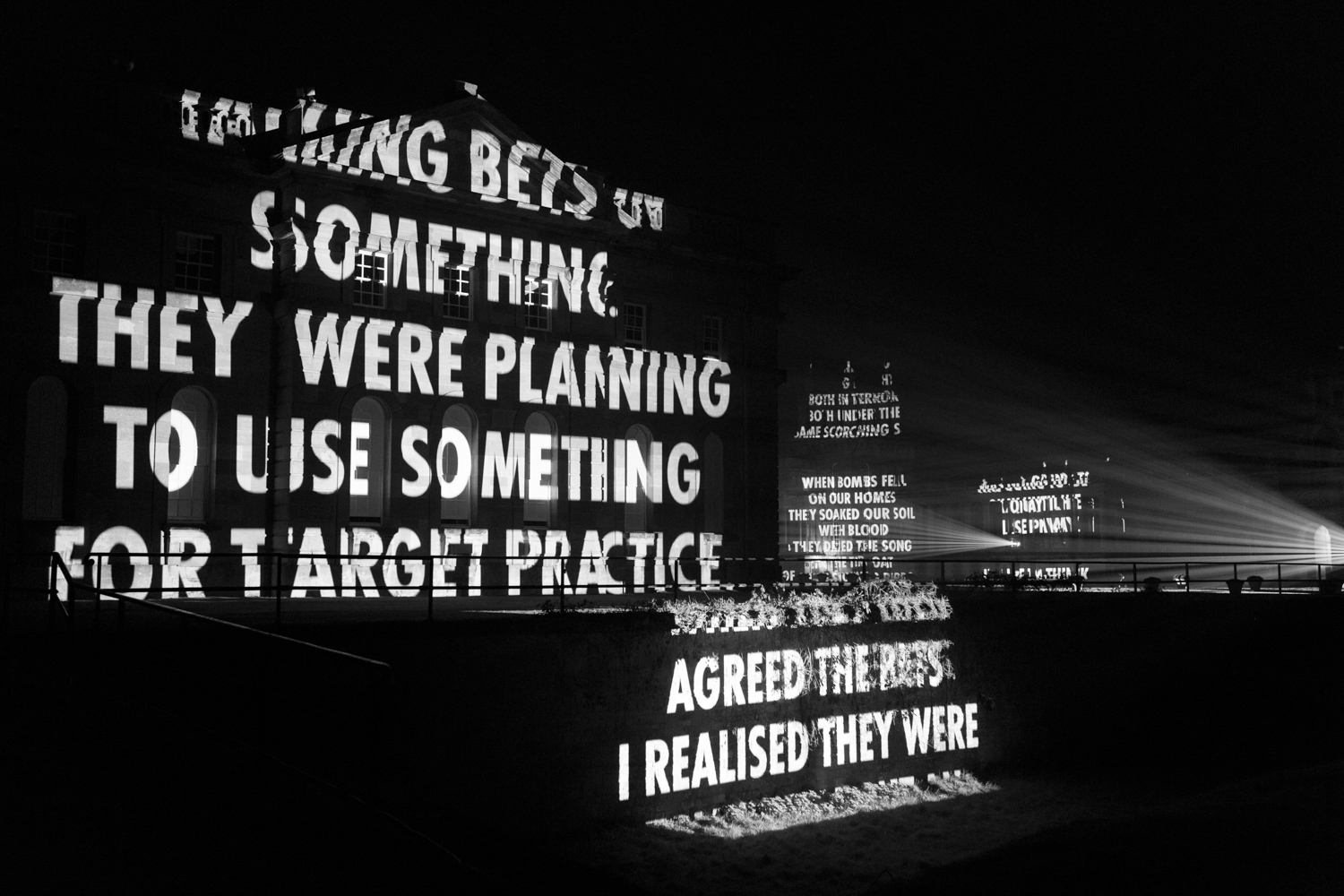

Jenny Holzer, ON WAR, 2017 (detail). Text: Interview conducted by Save the Children in Jordan, from case studies, © 2012–16 by Save the Children. Used with permission of Save the Children. All names have been changed to protect identities; “The Great Flight” by Abdalla Nuri, English translation by Jamie Osborn and Nineb Lamassu, © 2016 by the author and the translators, from Modern Poetry in Translation, no. 1/2016. Used with permission of the author and the translators. © 2017 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Samuel Keyte. Courtesy of the artist.

HOLZER-GLIER: I use text, not my own writing, because I believe in the power of first-hand accounts. What are the commonalities and differences [in the way we use text], Mom?

HOLZER: That we both are inclined to use first-person accounts by others, because they're vivid and true. That is a commonality.

HOLZER-GLIER: And I think we aren’t particularly interested in our own voices.

HOLZER: I hate my first-person. [both laugh]

HOLZER-GLIER: As do I.

HOLZER: All right. What are you reading or looking at now that's influencing you?

HOLZER-GLIER: Um, I'm reading Hillbilly Elegy I found in an airport, by J.D. Vance, that I think everyone should read. It's a perfect portrait of America, especially what's happening now. And you?

HOLZER: I'm reading text by very young school children from Philadelphia, because they say it like it is with no filters but with a whole lot of optimism.

HOLZER-GLIER: How research-intensive is your work?

HOLZER: I rely heavily on researchers. I couldn't begin to go as far as I want without a fantastic cadre of people who are smarter and more literate than I am.

HOLZER-GLIER: I research enough so I know what I'm talking about when I'm interviewing someone, but I prefer to speak to people, and that's how I learn, in sharing their stories.

HOLZER: You're more in the moment? That's good.

HOLZER-GLIER: On a day-to-day basis, how much do you talk to me about what you're making?

HOLZER: I like complaining to you about difficulties. [laughs] And once in a while, to celebrate when I don't create something ghastly.

HOLZER-GLIER: How much do I talk to you about what I'm making? Occasionally. I try to share successes so my parents don't regret paying my college tuition. [laughs]

HOLZER: I'm glad when you speak to me about what you're doing, but I want to respect your privacy. I try not pry until something is offered.

HOLZER-GLIER: I bet that's hard, as a parent—as I am learning.

HOLZER: Yeah. You don't want to seem to stay at a distance from one’s spawn's output. [laughs] But, on the other hand, you don't want to seem to imply that you, child, are doing nothing or doing the wrong thing or what you are doing could be improved—that's fatal to a relationship, I hear.

HOLZER-GLIER: Are we good critics of one another?

JENNY HOLZER: I think we're fair and balanced critics, affectionate ones, but knowledgeable critics.

HOLZER-GLIER: Yeah. You're kind, but I can tell when you don't like something—which is good.

HOLZER: As long as it's unstated, that's subtle and effective.

HOLZER-GLIER: Usually when you don't like something, you say, "Keep going!"

HOLZER: Solid advice. I give that to myself most mornings and at 4 AM—“Uh, keep going!”

HOLZER-GLIER: Jenny, you once said that in your work you "like for there to be hope as well as despair." Does that sentiment ring true to you, Lili?

HOLZER: You have to ask yourself now, Lili.

HOLZER-GLIER: Absolutely. And I believe in documentary work, which is what I mostly do. The point is to highlight a problem in society and hope to change it and make it better, so I absolutely believe in that.

Lili Holzer-Glier, Cook County Jail, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.C

Lili Holzer-Glier, Cook County Jail, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

HOLZER: A good thing about your work is you, at the very least, imply a solution, and that's cause for optimism and hope. Hang on—I want to ask some questions because that's easier than answering. What makes one of your works successful? What makes it fail? Let's talk failure now.

HOLZER-GLIER: This is the one I was—

HOLZER: Dreading?

HOLZER-GLIER: I hope most of the people I photograph are happy with their pictures and happy with how I've told their story. And I hope, like anybody doing documentary work, that it makes a difference and it will make some small change, or at least—

HOLZER: Go for medium change.

HOLZER-GLIER: Large change!

HOLZER: Even better.

HOLZER-GLIER: Highlight an issue, spur debate, hopefully spur a change. Failure is the opposite. If your subjects don't like how you represented them, if no one sees the work, no one cares, nothing happens. I think that's kind of the worst nightmare for me.

HOLZER: I appreciate that your work does all of those good things, and that you have that ineffable yet essential quality in your work, that it's made by somebody with an eye. To have people attend to it, it has to look right. You got that from... your father.

HOLZER-GLIER: [laughs] And what makes your work fail, Mom?

HOLZER: My work fails with some regularity. But I am reasonably critical of it, so I try to fix or kill the failures before they leave me.

HOLZER-GLIER: What's the biggest misconception about what you do?

HOLZER: A misconception is that the work is not visual, even sensual. I don't always succeed at visual, but I think it important, maybe mandatory, that people want to walk up to the work, see it, feel it, and not just read.

HOLZER-GLIER: I think a lot of people don't understand how much of a project manager you are, and how much detail work and how much research and how many contracts—all of this work you do that no one appreciates. They just think you sit in your studio and have ideas and that's it. No one thinks about the absolute grind and emails and everything else in what you do.

HOLZER: My noble crew and I have at least a double or a triple job, in that we have to conjure the art—that most mysterious of processes—but we also have to deal with frightening amounts of correspondence, contracts, and worthy and unworthy opposition. [laughs]

HOLZER-GLIER: This is definitely one I have to ask you: When was the last time a work of art made you cry, laugh, clench your fists and storm off—any emotion at its extreme? What was it and why?

HOLZER: This isn't about a work of art. The presentation in Washington by the Parkland students and others moved me more than anything has in years, and moved me because the presenters were spot on and identified what needs rapt attention; that not only is gun violence, it’s what beneath the violence in this country, including racism, sexism, money, money in politics. It's a national problem, not a school safety issue.

HOLZER-GLIER: I can't top that answer, and I don't look at enough art to have that sort of emotion, apparently. [laughs]

HOLZER: My turn. We both use photography—Lili, as your primary medium, and I use photography for documentation. Oh, this is a good one for you. Do you feel like you're back in school? What makes a good photograph? [both laugh]

HOLZER-GLIER: A good photograph for me is about content and relevance to what's happening in the world, and emotion. I believe in portraits and even in landscapes having a feeling—that is the most important thing.

HOLZER: I think a strong photo will elicit the appropriate emotion, or many, many feelings, be composed properly, and be humane, achingly sensitive, and available—somehow accessible.

HOLZER-GLIER: I think a weakness is photography is limits. One can never tell a whole truth, and it's always frustrating to feel like you just started scraping the surface of a story.

HOLZER: But that's not unique to photography. Art is seldom if ever as good as it might be, nor is any one individual, nor is any answer, just like this one.

Lili, what is the best piece of advice you have ever been given? And here's a maternal follow-up question: Do you follow it? And did it come from your mother? [both laugh]

Jenny Holzer, ON WAR, 2017 (detail) Text: Interviews with current and former members of the British military, © 2017 by the Not Forgotten Association. Used with permission of the Not Forgotten Association. © 2017 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Samuel Keyte. Courtesy of the artist.

Jenny Holzer, Ram, 2016. © 2016 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Collin LaFleche. Courtesy of the artist.

LILI HOLZER-GLIER: Oh, I have no idea. Do you have a good piece of advice? Have you given me any good advice? I probably need like 20 minutes to think of that.

HOLZER: I bet Joe Rodriguez gave you good advice—think back to his excellent tutelage.

HOLZER-GLIER: One thing that pops into my mind is more just wisdom. When I started getting jobs when I was like 18 or 19—and thought I was a cool hotshot—he said, "I'm happy for you princesa, you're talented, you deserve it, but what are you going to do when the phone stops ringing? That's what's really going to make you as photographer, what happens when people stop calling you." And of course I was like, "Well, why would people stop calling me?" [laughs] But he's absolutely right.

HOLZER: Meaning: What do you do when you have to pull it from within and do it because you're compelled?

HOLZER-GLIER: Yeah, hustle, make your own work, not because an editor is giving you a job and it's a finite thing and you get paid for it and then you go on to the next thing—when it's coming from you and it's a big story and you have to place it and you have to find the money and you have to do it because you think it's important. And he was so right. I'm at that point now, and I'm happy I'm here, but boy is it hard—and wonderful.

HOLZER: Do I recall correctly that he also said to get out of the building, go into the street, and find people, and let them look at you and you look at them in just the right ways?

HOLZER-GLIER: Always, and to have courage. His first assignment in his class is to take 11 rolls of film on the subway, portraits of complete strangers, just so you get over it—that sort of fear.

HOLZER: Here's a photo question, not on the list—how do you decide how close to get to people? What is intrusive; what is invasive; is it only fair to use the right lens to do a close-up of somebody's face versus putting a camera in somebody's face? How do you do that ethically, sensitively, properly?

HOLZER-GLIER: You're breaking my heart here, Mom. [laughs] That is one of the essential questions of doing this kind of work, and it's absolutely heartbreaking if someone is telling you about the deepest trauma of their life, and they're telling it to you, and how do you use that information? I think you have to be absolutely sensitive in the moment, and respond to how someone is feeling and talking to you, and there's explicit and implicit consent. I'll even pick up my camera, and kind of give them a questioning look, and often someone will nod, it's okay, or if they back away and shake their hand, then no. It's about being sensitive to people that instant.

HOLZER: That sounds about as right as it can be. I often wonder.

HOLZER-GLIER: You know, if you're sitting down and you're having a conversation with someone and someone has agreed to talk to you and be photographed, and they're telling you about their lives, it's different than just flashing someone on the street.

HOLZER: I hope so.

HOLZER-GLIER: It's a different scenario. But I want to know your best piece of life advice and if you follow it? It's a hard question.

HOLZER: That is situational—I'm going to dodge that one. [laughs] But that's the true answer. It's moment to moment, and my answer maybe is the same as yours. It depends. You have to be alert and alive, to the person, to the job, to the impulse - assuming the impulse is a good one. Here's the serious advice: Don't lose the ability to love.

Lili Holzer-Glier, Cook County Jail, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Lili Holzer-Glier, Cook County Jail, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

HOLZER-GLIER: I also want to say something about the idea of journalistic objectivity. I went to grad school for journalism, so objectivity came up a lot, but I don't believe it exists. I believe that people get involved in their stories. I was following an undocumented family for my thesis, and the woman had to walk five miles with her two little kids bring them to school and to go to work because she didn't have a car. It was cold. Often I would give them a ride because it's the decent thing to do. I got in trouble because I was involved in the story and instead I should photograph suffering. I understand that but I don't agree with it. I think if people are letting you into their lives in this sort of intimate way, it's more important to help people a little bit, and bring them coffee, or give them a ride. I know a lot of people disagree with me, but that's how I operate.

HOLZER: I would hope one could help and be objective. I don't want to imagine that those are mutually exclusive. Here's a bogus question: How did I feel when my daughter decided to pursue art? Are you making art now and not telling me? [both laugh]

HOLZER-GLIER: I've always been resistant to the term art and artist for obvious reasons; both of my parents are artists, and that's not something I thought I was pursuing. Obviously I work visually. One of the defining aspects of being an artist is it's about expression of self, and I don't really feel like I'm expressing myself in my work. I'm trying to tell other people's stories. It's about myself insomuch as I think a subject is important, but it's not about my soul and my angst and, you know, everything that goes into art. I know my parents disagree with me on this, but I believe my practice is a bit different—although I am on kind of the artistic side of journalism, so…

HOLZER: I think you've been contaminated by art and I'm glad about that. And I do think your soul and your mind and all of the body parts can and should be involved, and that doesn't subtract from what else you're after.

HOLZER-GLIER: Absolutely.

HOLZER: Oh, this question is maybe even worse: Would we ever collaborate?

HOLZER-GLIER: Absolutely!

HOLZER: Oh, okay.

HOLZER-GLIER: Well, we kind of have—

HOLZER: Actually, we did.

HOLZER-GLIER: In funny ways. I photograph your work for archival purposes, and, well, do you want to talk about the Wallpaper magazine thing?

HOLZER: One of our best collaborations was Lili photographing me with a chainsaw among sunflowers. Top moment in life. [both laugh] It's still a highlight—top of the tippy top.

HOLZER-GLIER: It was also 24 hours before I gave birth to my son, so it was a very heavy—

HOLZER: It was a pregnant moment. [both laugh] Is there anything else I'd like to say about Lili's work that I have not before?

Courtesy of Lili Holzer-Glier.

HOLZER-GLIER: Anything you haven't thought to ask?

HOLZER: Um, I think we're current.

HOLZER-GLIER: Yeah. I mean, I hope that you know… It's hard for a child to say this to a parent, especially one that's so incredible and extremely successful—

HOLZER: Blush blush. Cringe cringe.

HOLZER-GLIER: [laughs] But I absolutely admire what you do, and that there's so much content in your work that is important and relevant to today, and you have the courage to do that when a lot of art is not particularly relevant. And your work is beautiful, and full of content—I think that's admirable and I absolutely want to follow that in my own work.

HOLZER: Back atcha, Lili.