INTERVIEW WITH A PROJECTIONIST

BEN FAMA IN CONVERSATION WITH CAROLYN FUNK

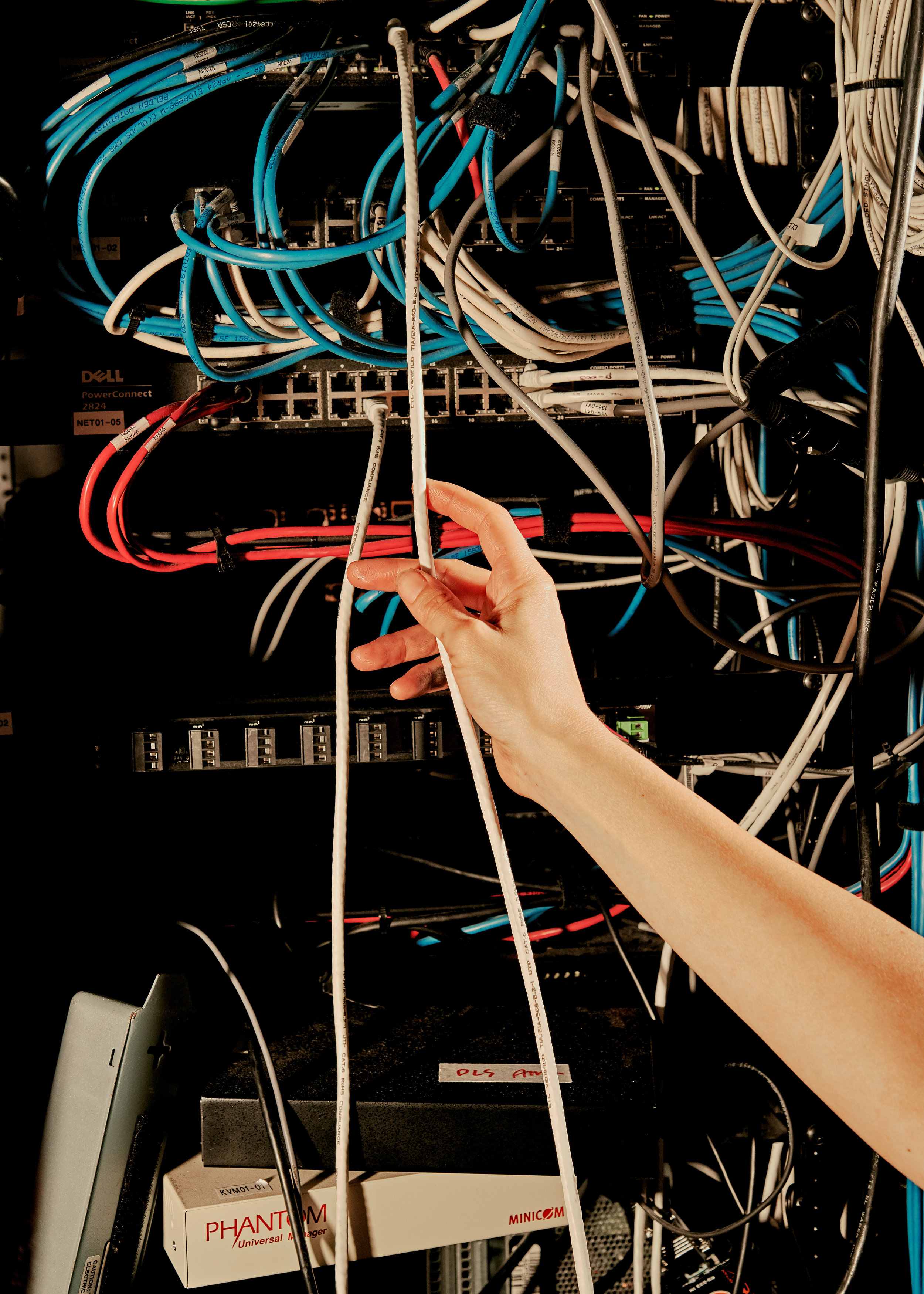

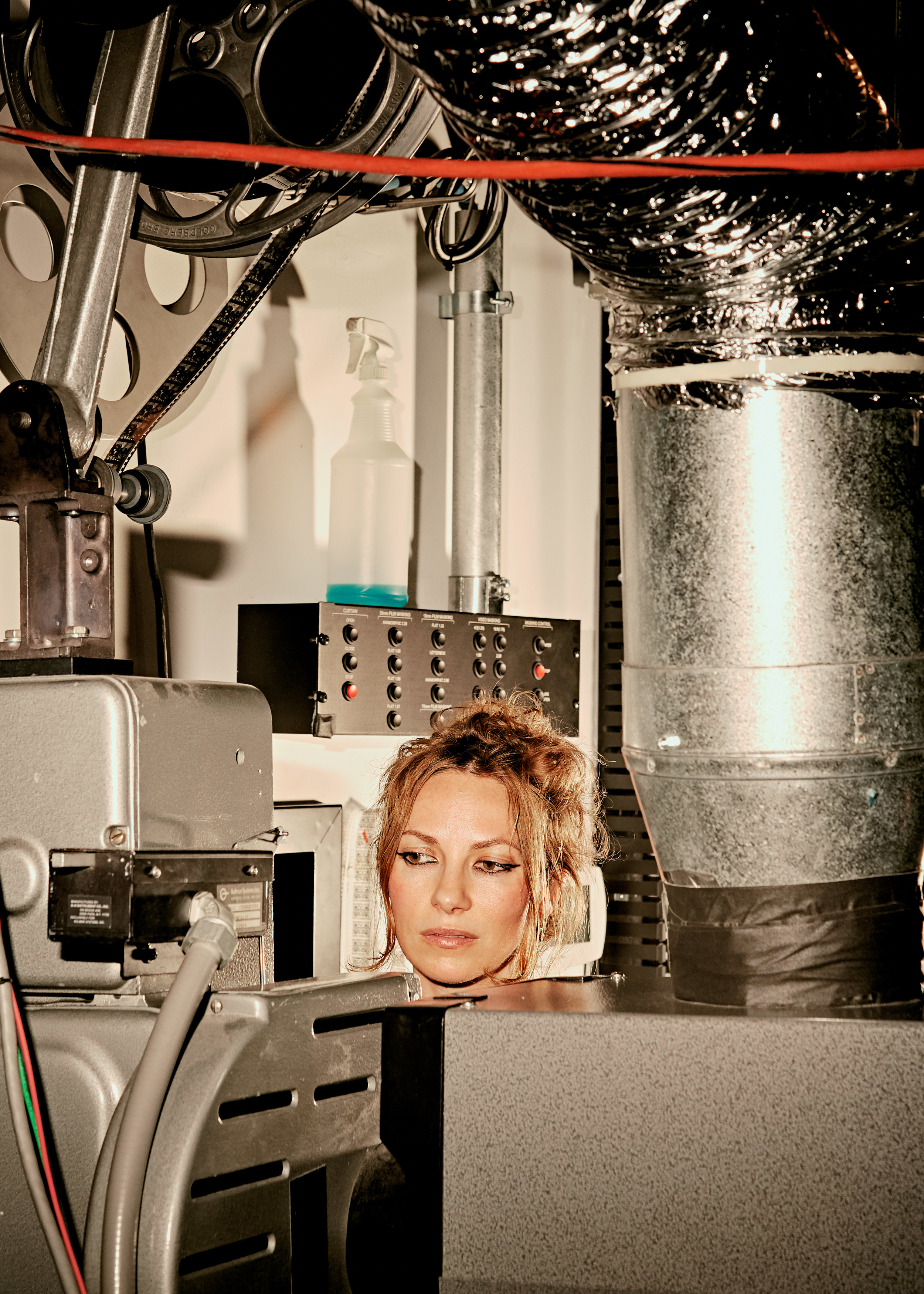

PHOTOS BY VICTOR LLORENTE

Photos: Victor Llorente

Carolyn Funk is a projectionist in New York City and around the country, including recently at the Museum of the Moving Image and Film Forum. She recently spoke to poet Ben Fama, whose recent book Deathwish was published by Newest York Arts Press in June, about her career. She and her workspace were photographed by Victor Llorente, who previously photographed escapes from New York for Newest York.

Ben Fama: Tell me the most chaotic thing that has happened to you in a projection booth.

Carolyn Funk: Any day as a projectionist has its own personal chaos! I use old machines and project several different film prints in a given day. There are so many variables. Two weeks ago the belt for a 35mm take-up reel broke — basically the reel stops turning and then film piles all over the floor. All film is basically considered archival in the digital age, so it absolutely cannot touch the floor. If it’s too late to turn the reel by hand you have to stop the show. Before digital, when film was mass-media, you might let the film run out on the floor; there might be an ocean of film over the floor. Any mayhem in the booth should stay invisible to audiences to prioritize the screening going on uninterrupted. Putting a spilled reel back together is like trying to put water back in a bucket. There are stories of projectionists dumping dropped prints in the dumpster rather than putting them back together. But those were the days of yore.

We’re running a 70mm series at MoMI right now, and last week both sound units failed right before the screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey. We scrambled to locate a unit in the city on a Sunday, install, and tech on the fly in front of a full theater. Sometimes an obscure film will arrive from India shipped in a burlap sack, loose reels, straw, film and fibers everywhere. Prints are old. The machines are old. Things break, I don’t really ruffle. The chaos is like white noise.

I was flown to Tampa to show The Hateful Eight in 70mm. My projection booth was the last to be set up in the country — and wasn’t. The sound equipment hadn’t been installed, the manufactured parts for 70mm didn’t quite fit, the lens was soft. For some reason there was water spraying all over and through the projector. I had to employ the kids serving popcorn to help me lift the 200-pound print onto the platter. The theater manager hated film, and therefore me. Somehow I was able to get on screen the next day, Christmas Eve. On top of all that I was working 16-hour days and living on English muffins.

BF: I have a lot of questions now! Was the manager/hater an anomaly? Is that type of resentment towards film common? 200 pounds seems really heavy… why is it so heavy???

CF: The Hateful Eight was run off a platter system, meaning all reels — the entire film — were built together to make, basically, one massive reel that sits on a giant, rotating table. Therefore I needed help getting that print onto the platter. 70mm is so heavy! I am showing Hamlet today in 70mm: it’s 4 hours (20 reels) long, and upon delivery with the reels weighed 803 pounds all together. At MoMI we screen everything archivally — reel-to-reel — using two projectors and a change-over system, so a massive film like Hamlet is (kind of) manageable.

The manager/hater in Tampa was an anomaly, but maybe indicative of tensions within the cinema distribution machines at that particular time. This manager had for years prior managed a chain multiplex in Times Square — and her husband had apparently been a union projectionist. There are rumors that she was involved in some underhanded bureaucratic wheelings and dealings in the midst of the commercial/institutional forcing-out of film for digital (thus cutting skilled labor at the expense of quality, history, and the entire medium of film) and this informed her doctrinary ire of film. The fact that Tarantino was bringing celluloid back to the mainstream and that film projectors — like those which AMCs and Regals had thrown in dumpsters just a few years before — were being re-installed, was a personal and professional battle loss. Swords crossed, hostility and intimidation tactics ensued! They were hot-breathing down my neck for the first 80 hours while I was trying to get the film up and running! By the end of the run, however, she did bring me some chocolates so I suppose there was a truce. And now after telling this story the mob is probably after me.

BF: I’m curious, is there a high learning curve to becoming a projectionist? It seems like a mix of art handling and a technical skill? Am I fantasizing or fetishizing this is as some sort of last “authentic” job?

CF: The big obstacle to learning film projection now is that the medium — film — has gone from ubiquitous to basically obsolete in the last decade. At the same time, or I suppose due to celluloid’s sudden rarity, there has been a move away from automation and platter systems to archival systems of reel-to-reel changeovers, and therefore a return to the traditional labor-intensive, skilled-trade aspects of projecting film. Which, yes! I think does make for the romanticization or fetishization of film projection in both Marxist worker and Hollywood analog nostalgic ways. I fetishize it all myself! And because of the intrinsic archival quality of all film now, projectionists have to act almost like archivists and experts on histories of film and film formats, as well as operators, presentation specialists, and technicians. So this does generate quite a learning curve! I was lucky that my first job in NYC was at Anthology Film Archives — I was there for 7 years and still consider Anthology my family — and that experience really functioned as a crash course in all of the above.

BF: Anthology is a theater that almost everyone I know has their own personal relationship too. Can you tell me a little about your life as a movie attendee? Do you go when you aren’t working to, say, Film Forum or Metrograph?

CF: To quote Barthes, “I don’t go very often to the cinema, hardly once a week.” I used to see at least 5 films a week in the theater, sometimes several in a day! It’s harder now that I work full-time in a projection booth. And when I do go I usually like to see something on real film, and more often than not, early Hollywood flicks over and over again. So I do end up at Film Forum a lot! I especially love a 30s double feature. I adore the programming at Metrograph but the assigned seating gives me intense anxiety, and maybe takes some spontaneity out of movie going. It’s fun to see films on the Upper West Side in general, and Walter Reade in specific, and my two absolutely favorite theaters to see films are the big screen at the Village East (it used to be Yiddish theater and is a landmarked building ah!) and the magical Jersey City Loew’s.

BF: You have Tallulah Bankhead’s name tattooed on your hand. It says “Tallulah” in script. As someone with tattoos, I’m truly envious. Can you tell me about your relationship to Tallulah?

CF: Tallulah is my glamorous bad girl role model!! — wild and utterly hedonistic, unapologetically scandalizing, constantly spouting bon mots. Tallulah was basically a pre-code film heroine in real life, like an unhinged Mae West. She always did exactly what she wanted and had zero inhibitions. So much bad behavior! She lived at the Hotel Elysee for 18 years with “a menagerie of men and beasts” including a pet lion cub named Winston Churchill, and set up shop in the Monkey Bar on the first floor, and regularly threw days-long parties. She once left one of such parties in nothing but an open mink coat. (Side note!! The Monkey Bar, one of my favorite places in the world obviously has a glorious mural featuring Tallulah among others, and incidentally is where I read Deathwish with a cocktail.) Her last words were “codeine… bourbon…” So I got the tattoo to remind myself to be like Tallulah, with varying degrees of success.