Haley Weiss

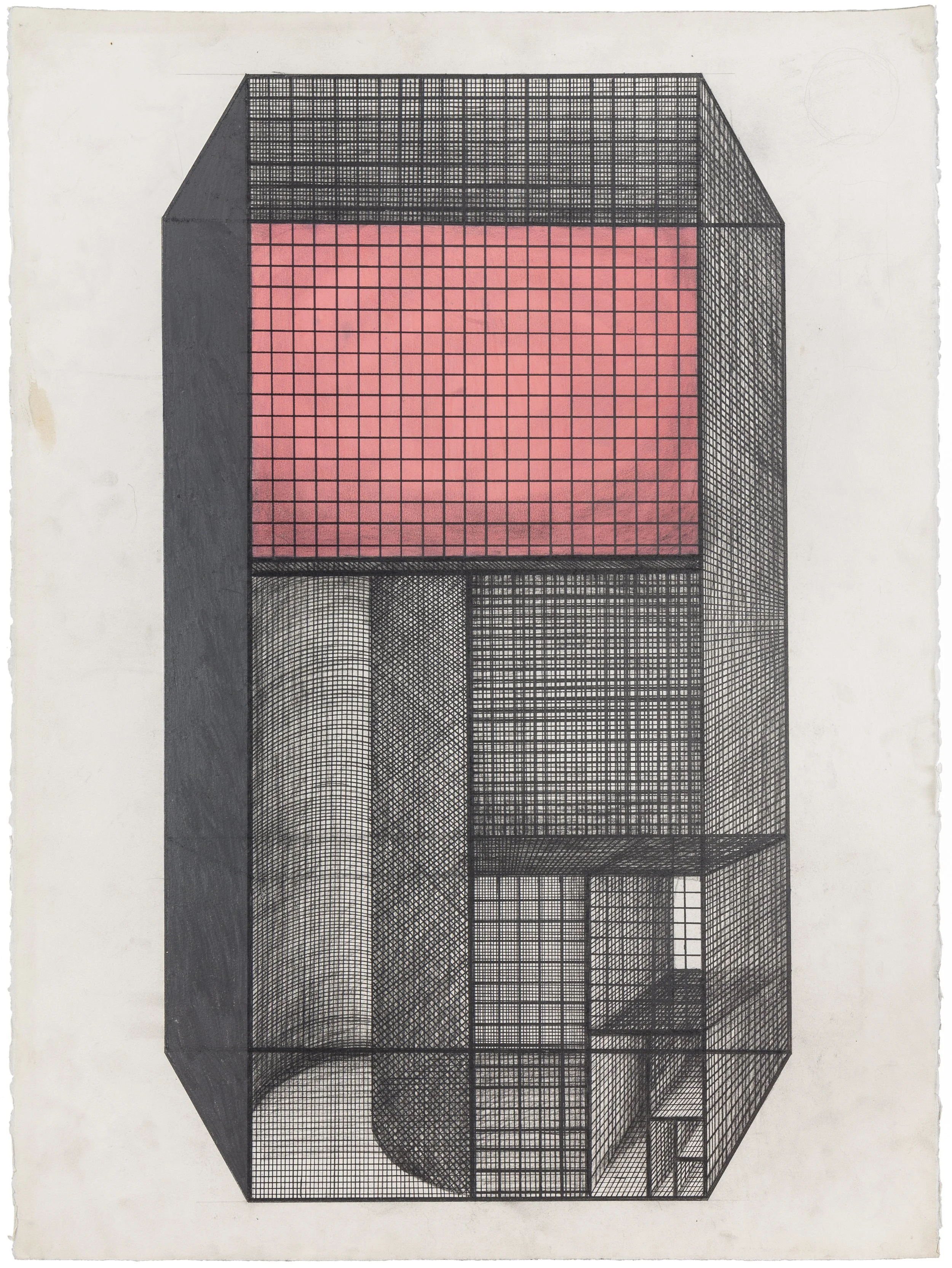

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Drawing for ‘Container of Perceiving,’ 1984. Acrylic, watercolor, and graphite on paper, 42 1/2 x 72 3/4 in. © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Columbia GSAPP.

"This mortality thing is bad news," declared Madeline Gins, the poet and philosopher, to the New York Times in 2010. It’s a bold statement, and Gins offered it for the obituary of her husband, the artist Arakawa. Together they spent decades collaborating on mind-bending architectural projects. Their spatial experiments, both speculative and realized (which Gins continued until her own passing in 2014), sought to oppose death in alignment with a concept of their own invention: “reversible destiny.”

According to Irene Sunwoo and Tiffany Lambert, the curators of a new show of Arakawa and Gins’ work – “Arakawa and Madeline Gins: Eternal Gradient” – reversible destiny is as surreal as it sounds. It can be defined most simply as “arguing for the transformative capacity of architecture to empower humans to resist their own deaths.” The exhibition, which opens today at Columbia GSAPP’s Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery, features previously unpublished material with a focus on the duo’s preparatory hand drawings from the '80s. Sunwoo explains that this is a time when Arakawa and Gins’ “energies converged in the realm of architecture.” While the works included seem to exist in a sci-fi universe of their own, the logic of that world is somehow sound; Arakawa and Gins were both interested in the body and biology, how people move through and perceive space, and these creations seem to say don’t be too comfortable, get knocked off-kilter, and see your surroundings afresh. (In the case of the duo’s later works that came to physical fruition, like this public park in Japan, you might literally get knocked off of your feet.)

Is there anything to this idea of reversible destiny? Can the very walls around you stall your inevitable demise? We recently spoke to Sunwoo, who’s an architectural historian, and came away with three points of departure for Newest York readers – an introductory guide to reversible destiny, if you will. We invite you to start here with the knowledge that there’s much more to explore, even within this precise slice of Arakawa and Gins’ body of work.

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Study for ‘Critical Holder,’ 1990. Acrylic, graphite, and color pencil on paper, 42 1/2 x 61 in. © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Columbia GSAPP.

1. Reaching Your Own Reversible Destiny

"It's possible to imagine a new relationship between the body and architectural space other than what we have been accustomed to for centuries or millennia," Sunwoo says. "By creating those new relationships and experiences, we have the potential to have different psychological, perceptual, biological, and emotional responses and experiences, which could totally change the direction of our lives – our mortality in that sense. It's not a biological process where time is reversed – it's not a Benjamin Button situation – it's much more conceptual than that, and spiritual I would say as well. But I think the important takeaway is that there is this belief that there is a different type of life possible and that architectural space can somehow make that realized."

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Screen-Valve, 1985-87. Graphite and acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 1/2 in. © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Columbia GSAPP.

2. Playtime

"I think [play] was always central [to Arakawa and Gins’ work], even looking back at their paintings and poetry. A lot of Arakawa’s paintings are these puzzles or mind games, using language and stripped-down imagery; it wasn't pictorial necessarily, but these visual and semiotic puzzles. And then with Madeline's writing – and I'm by no means an expert on the literary side of things – it’s in the layout of some of her poems, the way that punctuation is used. For example, I found a letter where she as apologizing to someone for the delay in getting back to them and she had spelled out delay with a 'D' and several hyphens, an 'E' and several hyphens, an 'L' and several hyphens, and so on and so forth. So in images and language, play was always there. In spaces it's happened as well, because there's a delight that happens when you are thrown off balance just a little bit; it's this element of surprise that I think goes back to the concept of reversible destiny to use triggers that make you see your environment and yourself in different ways. [In my experience of their physical works,] your body really is forced to function in a different way, so much so that sometimes you have to grip onto the walls to keep yourself from falling down. Your body is constantly active, and your mind too – that was part of the intent, I think.”

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Perspectival view showing entrance to ‘Bridge of Reversible Destiny,’ 1989. Graphite and collage on vellum, 24 x 30 in. © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Columbia GSAPP.

3. A New View

“The essence of [reversible destiny is] a sense of empowerment over your own state of being in the world and understanding all of your intellectual, physical, psychological, and social capacities – and to shake things up so that life doesn't seem like a one-way path. It's much more dimensional than that and can go in any direction possible; that was the message that I was getting from it, and I would subscribe to that. It is really so centered on the individual and the body and its own capacity, rather than just accepting all of your surroundings and conditions. I think it's a call to wake people up."

“Arakawa and Madeline Gins: Eternal Gradient” is on view at Columbia GSAPP’s Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery from March 30, 2018 through June 16, 2018.